Eqbal Ahmed

[Dawn, 19 May 1991]

It is reassuring that earlier this week Pakistan’s President and India’s Prime Minister attempted simultaneously to dispel rumours of an impending war between the two neighbours. Their awareness of war’s destructive potential and inconclusive outcome is among the few signs of hope that this catastrophe can be averted.

If it comes, the fourth India-Pakistan war shall undoubtedly be the most destructive. The armies of the two countries are bigger and armaments are more plentiful and sophisticated than ever before. Chances are that they would slug it out for at least six weeks, possibly longer. Conservative estimates are that each day, each side shall expend no less than rupees three hundred to four hundred crore. Losses for their overall economies could be much greater. The human costs and outcome are unpredictable. Recovery would take decades.

Although in the past Delhi and Islamabad have observed mutual restraint – e.g. in 1965 and 1971 both sides refrained from destroying each other’s industrial including defence-oriented installations – the use of nuclear weapons cannot be excluded. Both countries are presumed to possess nuclear capability and they harbour extreme distrust of each other.

Once it starts, war is subject to the logic of escalation. This rule may apply especially in the Indo-Pakistani case. Both sides are inclined to view the next war as their most decisive and final conflict. Furthermore, most Pakistanis including many decision-makers and senior soldiers are persuaded that India has not come to terms with the very existence of Pakistan. Last summer, I was also surprised to find influential Indians arguing that the stake in Kashmir and Punjab is nothing less than India’s survival. These extreme estimations could cause desperate behaviour. Also, the compulsion to pre-empt first strike by the other side poses a major risk of nuclear holocaust.

The logic of war lies this time in India, not in Pakistan. It has to do with Kashmir, and with the fact that in the near future India is likely to have a succession of weak governments. They will not be able to take the tough political decisions which are necessary to resolve the question of Kashmir, and settle India’s outstanding disputes with Pakistan. The old adage, about war being a continuation of politics by other means, rarely applies. In our time, war signifies failure of politics, and India appears to be dangerously embarked on the path of political failure.

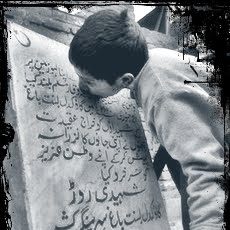

By mid-1991, India has inexorably lost the struggle for Kashmir, much as France had lost the struggle for Algeria by 1950, and by 1964 the United States had lost in Vietnam. In wars of liberation, losses and gains are calculated not in terms of who controls what territory. Rather, they are measured in terms of who commands legitimacy and who occupies the hearts and minds of the people inhabiting the disputed land.

That is why strategists of guerrilla warfare have consistently emphasised the primacy of politics over military activism; and insisted on evaluating even military operations in terms of their political impact rather than in the conventional terms of battles won and lost. In our time, armed insurgents rarely seek to defeat the incumbent regime militarily. Their aim is to delegitimse the enemy and gain legitimacy for their cause. The two processes are organically linked.

Legitimacy does not refer to the popularity of the incumbent state but its very title to govern. When legitimacy declines and the moral isolation of incumbent states becomes widespread, its armed forces are compelled to police the population – an activity professional soldiers find onerous and demoralising.

When they are pitted against guerrillas who enjoy popular support, professional armies follow a vicious logic of escalation. The elusive enemy puts into question not only their effectiveness but also the validity of their training and organisation. Professional armies trapped in the ambiguities of guerrilla warfare yearn for the certainties of conventional battles. Moreover, the morale of professional soldiers cannot be maintained if they realise that they are fighting against a popular rebellion. They develop the compulsion to make believe that the guerrillas are trained, equipped, and directed by a foreign power; and that they gain popular support by widespread use of terror. This belief produces two responses – counter-terror and war.

Counter-terror entails widespread violation of civilians whose support underlies the insurgents’ perseverance. But as a method of regaining the consent of the governed, brutalisation – which in case of France in Algeria and America in Vietnam reached genocidal proportions – invariably backfires. It alienates the people irreversibly from the state which so torments them.

As the moral isolation of the incumbent state becomes irreversible, military and civilian officials engaged in counter-insurgency are increasingly tempted to draw the presumably ‘real’ enemy into open battle. Carrying the war to a sovereign nation – presumed fountainhead of the intractable insurgency – becomes their most compelling and only road to a conventional showdown. They begin by seeking to destroy the ‘external sanctuary’ of the insurgents. Thus starts the dynamic of escalation which often ends with a full-scale invasion of the country whose support is deemed central to persistence of the insurgency.

It was this process that led France to invade first Egypt, then Tunisia. These same compulsions led the United States to wage the air war against North Vietnam and finally invade Cambodia. India is fast approaching that point. In fact, low intensity raids on the presumed sanctuaries across the line-of-control in Kashmir have already begun.

The alternative to increasing repression and military escalation is to seek a political settlement. But there are many more constraints on governments against negotiating with another government. Therefore, it takes especially strong governments, and leaders with a sense of history, to reach an accord with its non-governmental adversary. A succession of French governments failed to enter into serious discussion with the Algerian FLN until General Charles De Gaulle came to power, and negotiated France out of the Algerian quagmire.

Indian leaders would do well to remember that as the French perceived it. Algeria was not a colony; it was an integral part of France. Unlike Kashmir, Algeria was not an internationally disputed territory; it was a French province – department. A million ethnic French people had actually settled there and hundreds of thousands of Arab Algerians had remained actively loyal to France. They were joined by millions of French “ultras” who had apocalyptic visions of France’s fall from grace if it were to give up on Algeria Francaise. Yet, De Gaulle had the wisdom to realise that France had lost legitimacy with an overwhelming majority of Algerians, and that this loss had become irreversible. France’s interests were better served by his courageous recognition of this stark reality. It was able to avoid the kind of humiliating debacle the United States suffered in Vietnam. Its moral stature rose, its relations with Arab North Africa improved, and its influence in the Maghreb expanded.

But there is no De Gaulle on the Indian political horizon. We must, nevertheless find ways to maintain the peace between India and Pakistan, and bring relief and justice to the beleaguered Kashmiris.